A new approach to identifying the risk of infection by a parasite in Brazil could improve the country’s efforts to control a lethal disease.

A team of international researchers led by Gustavo Machado, assistant professor of emerging and transboundary diseases at NC State’s College of Veterinary Medicine, have developed a mathematical model to predict the number of people who could develop visceral Leishmaniasis, which is fatal in more than 90 percent of cases if left untreated. The findings, published in BMC Infectious Diseases, could be used by the Brazilian Ministry of Health to shape future surveillance and mitigation strategies.

The new model allows researchers to map at-risk human populations in each Brazilian municipality by examining factors such as population size and range of parasite transmission. This approach improves the accuracy of Brazil’s current risk classification system, which previously did not consider the possibility of disease transmission between neighboring municipalities.

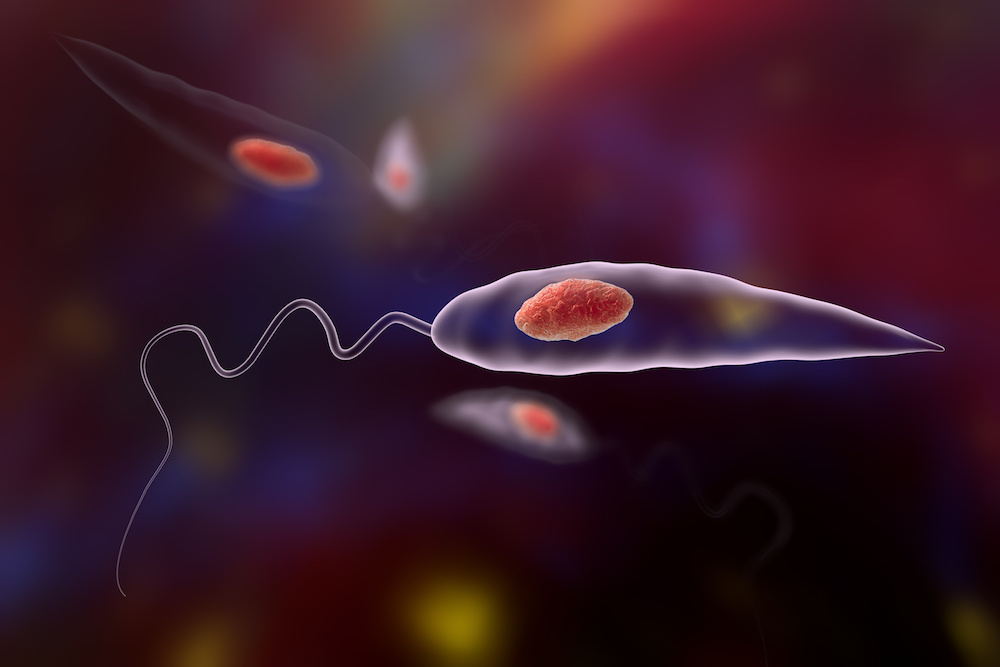

Brazil is ranked second worldwide in prevalence of the disease and is home to 95 percent of total occurrences in the Americas. The parasite responsible for the disease is Leishmania, which is transferred between animals and humans by sandfly bites. After being bitten by infected sandflies, animals and humans act as reservoirs for the parasite and carry the disease to new areas.

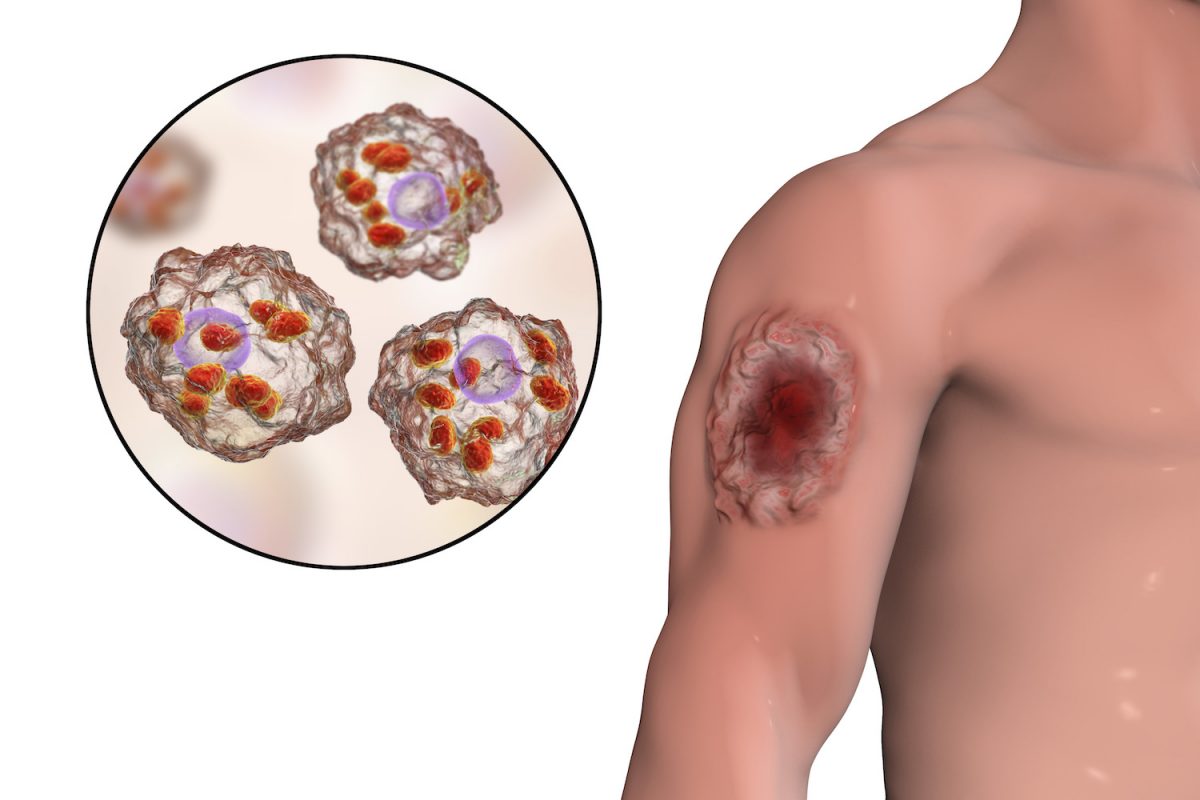

A close-up view of Leishmania amastigotes-infected human histiocyte cells, 3D illustration.

Using their mathematical model, the researchers showed that within 10 years the disease has spread to southern Brazilian states where it has never previously been reported – a problem that may have been exacerbated by inaccurate risk prediction.

“What we found was a weak correlation between the current risk classification system and our new approach,” said Machado. “Importantly, we found the largest disagreement in areas of transmission or high transmission risk, meaning the current method of national risk classification is significantly underestimating the number of high risk areas.”

By highlighting more high-risk areas, the new model could help prevent the spread of the disease by redirecting the country’s resources to key areas. Machado is developing similar approaches to tackle other diseases such as Leptospirosis, which is another major public health concern in Brazil.

In urban and rural areas, large numbers of stray dogs could increase the risk of sandflies transferring the parasites to humans.

The study also emphasizes the need for improved surveillance of visceral Leishmaniasis, which could provide insight into how the disease spreads and how it could be stopped. In urban and rural areas, dogs are the main reservoir of Leishmania and, as Machado and his collaborators have shown in a previous study, the presence of large numbers of stray dogs could increase the risk of sandflies transferring the parasites to humans. A recent strategy under consideration is using insecticide collars for dogs, but, as Machado explains, without surveillance to guide where and when to distribute these collars, the impact will be difficult to see.

The research team is now considering new investigations to improve the surveillance and understanding of the disease in Brazil.

“What we are trying to propose is to start in a small area in Brazil and build capacity,” said Machado. “I believe we can give them tools like this small-area mapping approach, which could make their surveillance more effective in the long run. ‘

– Greer Arthur, Global Health Program Specialist

Original article published on January 3, 2019, in BMC Infectious Diseases.